Ethno with Abby

I am a humorously tired ethnomusicologist and professor.

Here, I write in an attempt to contextualize the world around me through the lens of music, sound, and my experiences.

Visit here for my professional site.

Trying to Tremor: Alternative Identity and Alternative Music in São Miguel

The Black Atlantic Traversing African American Popular Music

OTHER RECENT WORK

Other Topics

Jamaican Dancehall MasculinityDebussy and Parisian Musical Consumption at the Fin De SicleThe Soft Battle Cry of an independent Christian tour

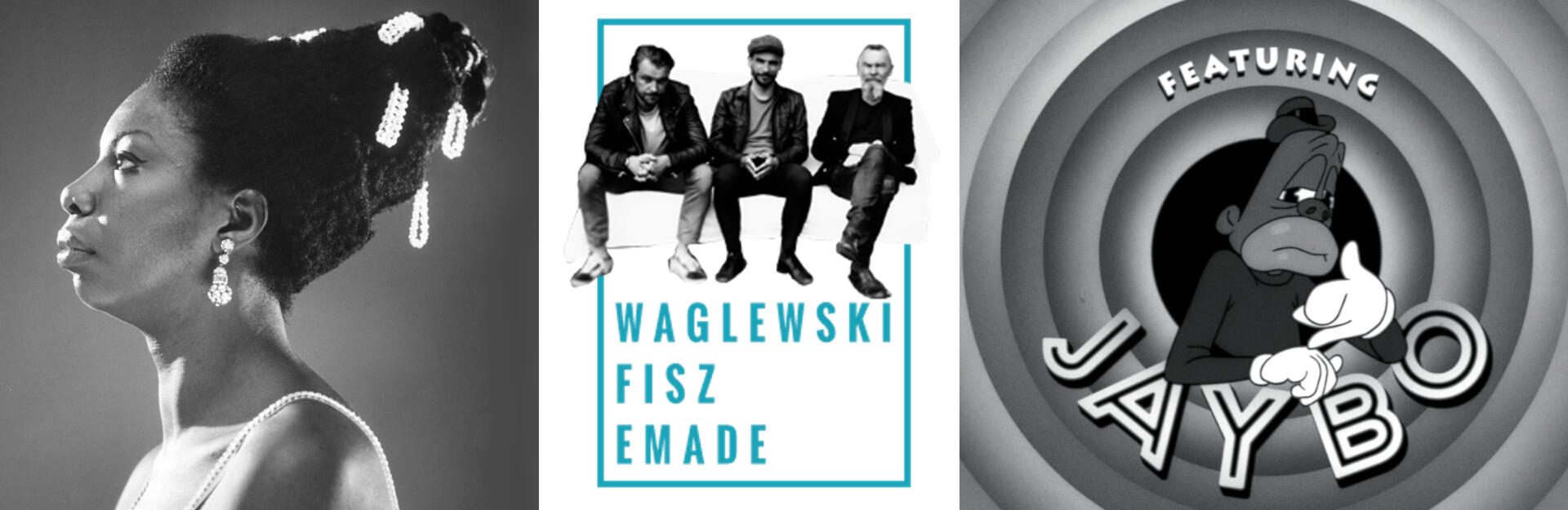

Four Women, Three Songs: Nina Simone Sampled in Polish and American Hip Hop

Excerpts provided below. Please write for permission to use.Regardless of intended motivation, meaning is manifested in the use of established musical material through sampling. Such us the case with Nina Simone’s musical catalog, which is frequently used by hip-hop artists to further their musical messages, despite the contentions between her personal politics and the hypermasculine and often toxic rhetoric of the genre. One example of Simone’s work used in hip-hop is rapper Jay-Z’s (hereafter referred to as Shawn Carter) 2017 song “The Story of O.J.,” a racially charged ode to black self-elevation and financial reflection with an animated video of racial stereotypes to boot. This song uses Simone’s rich contralto from “Four Women,” a song released in 1966 about four female archetypes with varying intersectional implications. This song was also sampled by Polish rapper Fisz and producer Emade for the 2008 song “Heavi Metal.” What power does Simone’s musical material have in these two hip-hop applications? Does her voice make a difference in the context of African American or Polish hip-hop? Does the sample add meaning or is its value based on something else?The repeated use of the same music for sampling reflects the fluid, shared, and boundless connection of musical sound and how it can be used to conceive new creative materials. Cultural ripples are caused by the flux of musical meaning over time and across cultures due to the use of sampling and creation of previously established musical styles in different regions. In this way, Simone’s voice in Jay-Z’s song over forty years after its creation still elevates black power and progress, while simultaneously being recognized in a more static state for its objective beauty (as sound) by Fisz, with both applications reflecting the dynamics of a global hip-hop community. The original meaning of the song can serve to support a new work or be relegated to meaninglessness: this is the power of sampling. In these new roles, Simone’s voice can carry a new identity based on cultural application, ever tethered to her black female identity through her sound but not necessarily through her message.Polish hip hop began following the end of communism in 1989, liberating exposure to Western popular culture throughout the nation, leading to the sale of African American hip hop records in major cities like Krakow. Throughout the 1990s hip hop rose to prominence as a way for the “powerless and poor” to “resort to radical methods” to “articulate their interests” despite being “described as uncouth and ignorant of the new socio-economic reality.” Two elements of hip hop culture existed in Poland prior to the music: graffiti, as an aspect of resistance and protest since the 1980s, and DJs, who were popular in Poland’s thriving disco scene of the late 1970s and 80s. Breakdancing and emceeing came later, introduced by films portraying African American culture and popularized by Poland’s “selective fascination of western trends” that is still elevated through the use of social media websites like YouTube and SoundCloud. Since Poland is “virtually all-white,” hip hop lyrics “barely touch[ed] on familiar American themes of police violence or racism,” but youth’s performed their own version of supposed ‘blackness’ by resisting idealized presentations of the world and their Polish culture.Nina Simone’s “Four Women” has been a rich site of musical exploration for multiple artists, and it was not even her most popular or impactful song. But to understand the impact of her work, it is paramount to understand the power of the woman. Simone was unapologetically expressive, unapologetically woman, and unapologetically black. In this way, she challenged acceptable forms of female performance with an idiosyncratic stage presence, bursting with spontaneous dance breaks and pianistic improvisation. The spectacle is capturing but so is the sound, reflective of an unquenchable appetite for musical exploration that started from the age of three (when she began to teach herself piano). Simone flourished as a local celebrity throughout her youth in Tyron, North Carolina after a piano teacher nurtured her musical skills and put her piano playing on display at her mother’s church. These musical roots shaped her diverse and experimental musical style, which often juxtaposed seemingly opposing genres (like soul and show tunes for “Mississippi Goddam”) to create moving pieces on common musical topics and her activist interests.Nearly 140 songs sample Simone’s work, the majority being hip hop artists who use her sound to “[mark] their virtuosity and political allegiances” since “sampling’s aesthetic project is one of recombination and recontextualization, and the notion of creativity must be parsed through the parameters of this project.” The combination of Simone’s vocals and instrumental arrangement then provides its distinct qualities to the work of hip hop artists, who also benefit from her cultural capital and reputation, whether they do so consciously or unconsciously. Sampling Simone’s work, and that of other female vocalists and instrumentalists, is one way “women have influenced rap style and technique, ultimately shaping aesthetic standards and technological practices,” although “pre-existing masculinist scripts and sexist practices” have “ensured the greater visibility of men’s prerogatives and perspectives relative to women’s.” The “manipulation by contemporary music-makers” means Simone’s voice is not connected to her embodiment or presence, but instead represents “sound-as-object,” placing her in the realm of representing a time, a feeling, or something other than just herself – a common understanding of recorded song.The lyrical content of Carter’s "The Story of O.J." is not focused on any messages about women in an overt sense, but the video imagines women in predictable roles. One heavy-set woman labors as the “mammy” figure, while another voluptuous female parades around a burlesque stage with a crowd of men ogling, wearing only a thong and pasties on her breasts with hair styled like a flapper from the 1920s. She is the precursor to the “hoe” figure often described or seen strutting around nearly naked in other hip-hop videos. The mammy figure has dark skin and is seen washing clothes: she is “Aunt Sarah.” The other woman is shapely, confidently strutting across the stage to perform her sexuality for a crowd of screaming black men: she is “Sweet Thing.” Simone does not fit neatly into her own proposed archetypes or those often presented in hip hop visuals because her art or her voice and cultural standing set her apart from the other women.Miles White describes Jay-Z as an artist who offers “intimate and candid portraits of his life in song,” detailing his experiences growing up in Marcy Projects in Brooklyn, NY and gaining street credibility “of having risked his body in performance” as “the outlaw” or “antiheroic figure and a powerful masculine actor who succeeded against the odds and lived to rap about it.” His early work showed him embodying this archetypical black man raised by the streets who turned his past into a success story. This song embodies the successful aspect, with wisdom that reflects an awareness of the circumstances that changed and those that were beyond his control. Carter “rhymes about the narrative arch of his own life… used as raw materials of aesthetic performance.” Is it possible that in creating stories about his life for his own betterment and to fight the dehumanization of people like him, women were not equally considered?Fisz (whose real name is Bartosz Waglewski) regularly samples American music, sampling from different decades including the 1960s and 1990s. “Heavi Metal” details Waglewski’s experiences in middle or high school, describing moments of innocent excitement and embarrassment with a playful, childlike perspective. Lyrical delivery comes in wandering, choppy fragments. Waglewski is the narrator, in opposition with the intentions of other boys, seemingly unpopular, and observing the roles of his classmates and teachers as though he was separate from the environment. The first verse introduces a female interest that has matured and begun receiving attention from boys. It is not overtly stated but seems like the narrator is fond of this girl. Some meaning may be lost in translation, like the meaning of “tauzen” or how popular the athlete Górnik was in the era the song describes.The nostalgic mood of the song is still salient, further understood in the second verse, which describes “a fog” of fragrance from the female interest before repeating the line “God created her, Satan possessed her.” This line is stated once in the first verse, twice in the second verse, and once again in the third verse. The line “your dress was a huge scandal” also appears repeatedly, giving the impression that the narrator is thinking back on a meaningful memory of this female subject. He describes a “flame” in his gut when “[he] felt [her] bra on [his] back” and describes this female’s “dress and knee-highs” as famous. These moments are playing in his head and he is putting them to words. It is a song of forlorn prepubescent angst, poetically stretched over a looping beat by his older self. More time has passed to process the experiences but the fact that his desire for this female is incomplete still resonates in his jagged lyrical delivery and in the musical sound.The reflective position Waglewski takes removes him from the dominant idiom of hip hop masculinity heard in “The Story of O.J.” Instead, his story details the development of masculine identity, something that may present similar markers to hegemonic masculinity in America. His character in the song wants female attention, observes male competition (through athletic completion and boys bidding for the attention of his female interest). These are common traits of masculine behavior, but the overarching feeling of uncertainty and wavering confidence reveals an incomplete understanding of motivations (for the behaviors he describes). Waglewski describes the events with the wisdom of his adult self but embodies the mentality of his younger self to develop the narrative in a relatable frame. Simone’s voice is not elevated in this application but it is not disrespected either. I argue that it is neutral in relation to messages in her life and legacy. Removed from intentions of furthering any musical or embodied agenda, Simone’s voice simply is, present in this context along with her musical material that sets the nostalgic tone Waglewski desired. Her original instrumental with piano and bass is slightly sped up and made more jubilant with the addition melodic riffs on a solo flute – repeating throughout the duration of the track. Her identity, as presented by her voice, is not the focus in this song.Selected Bibliography

Mahaliah Ayana Little, “Why Don’t We Love These Hoes? Black Women, Popular Culture, and the Contemporary Hoe Archetype,” In Black Female Sexualities, edited by Trimiko Malancon and Joanne M. Braxton (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2015).

Vanessa Chang, “Records that Play: The Present Past in Sampling Practice,” Popular Music 28, no. 2 (2009).

Covid Grieving and Jamaican Pentecostal Breath

This paper was recently presented at the 2021 Society for Ethnomusicology (SEM) Annual Meeting.

Excerpts provided below. Please write for permission to use.In Jamaica, over two million people are religious, with the majority being Christians. For many, religious associations are automatic, something you adhere to from your youth and carry into adulthood, existing as a part of your identity whether you are “a yard” (in Jamaica) or “abroad” (in a foreign country, which is typically understood as the US, Canada, or England: three countries with a large amount of Jamaican immigrants. Many funerals were cancelled in Jamaica during the pandemic, despite the continuation of graveside gatherings. True to their namesake, these events take place where the body will be buried and usually feature huddled masses singing, eating, telling stories, and generally connecting in an open-air environment with the shared cause of celebrating a loved one.In August 2021 another uncle, David (my mother’s brother), died in England. My mother and two of her sisters were visiting St. Mary, the country Parrish in Jamaica where my family is from. In the absence of his body, they gathered at the family plot where my sister and grandparents are buried and sang songs to celebrate their brother’s life. They cooked a large meal, killing a goat to make curry along with a bounty of sides. They invited neighbors, many of whom grew up with David and were shocked by his passing. This communal celebration style is common in my family and in the practices of Pentecostal Jamaicans, translating traditional worship practices to the context of mourning. Professor and ethnomusicologist Melvin Butler states:“In Jamaica and the United States, Pentecostal Christianity, like other religious traditions, has been shaped by the particular social and historical circumstances of those who practice it. It should come as no surprise that Jamaican Pentecostal sometimes embrace musical styles and repertoire that feel strange and unfamiliar to African American church goers. Likewise, African-American Pentecostals tend to enjoy gospel songs that differ from the music their Jamaican counterparts prefer.”He further states “in Pentecostal church services, music-making is also a form of spiritual communication through which believers attempt to feel God’s presence and acquire ‘heavenly gifts’ that will uplift and empower them.” The arrangement of Uncle Carlos’s service, performance of grief, and structure of musical delivery and performance are shaped by interactions between African-American and Jamaican Pentecostalism, a reflection of the cultural practices of those in attendance and the shared desire to spiritually connect with the same God: across cultures and through sound. This cross-cultural religious and cultural celebration was not as salient at my Uncle David’s gathering, but the presence of a common musical idiom persisted regardless of which family members were visiting from “abroad” or just gathering “a yard.” Within my Uncle Carlos’ service last September, a shared desire joined Jamaican and African American Pentecostal worshippers in different way, reflecting the reshaping of both cultural approaches to center on a product that was culturally consumable for all in attendance.Within this service guests all operated at different levels of awareness, somewhat based on their engagement, that shaped how they received and interacted with aspects of the service and the music selected. The congregational hymns were known and performed by both Jamaican and African-American guests who were in attendance, intentionally selected to bridge a cultural gap. Both cultures make spiritual and collective meanings from the performance of gospel music and how the body communicates worship. Musicologist Andrew Legg calls gospel music “one of the most articulate expressions of history, culture and community,” further elaborating on the potency of this style with a focus on the gospel singer. He creates a taxonomy of musical gesture in gospel singing, elaborating on the effects and function of grunts and moans, shouts, shifts in timbre, song-speech, and vibrato (among other things). Many of these elements were present in songs heard during the service, performed by individuals and by the entire congregation.The body is a vehicle for worship as the voice is. Legg’s appreciation for the controlled use of these elements is not singular, as the quality of a vocal performance is something everyone within the congregation of a black church is prepared to determine, sometimes, with nothing more than a facial expression. The opening and closing hymns were part of a program that featured two solos interspersed among tributes, a eulogy, prayer of comfort, and brief message, which typically concludes with a call to salvation. While congregational songs, like the opening and closing hymns, allow patrons to perform with a singular goal and mutually lift their spirits with a shared voice bellowing throughout the sanctuary space, elaborate solo performances allow mourners to meditate on their thought, what they hear, and memories of their loved one.Virtuosic vocal delivery and powerful use of gesture was present in the solo performance of “We Shall Behold Him” by Patrice Brown, a member of the Metropolitan Baptist Church and a singer my Uncle Carlos loved to hear. Brown’s solo makes use of “the vamp,” which professor and gospel scholar Braxton D. Shelley describes as a “climactic musical unit central both to the experience of gospel song and to many black Christian liturgies, to illuminate the interrelation of form, experience, and meaning in African American Christians.” This musical feature is presented with the intention of allowing the audience to transcend the space, the performance, and the present reality. It is engrained in the African American gospel vernacular to the point where both performer and audience find the feature to be commonplace but welcomed. Performances like Brown’s touches listeners in a different way than the congregational songs do, and there is a connectedness between performer and audience in the flow of improvisation in the flourishes and vocal runs that goes beyond entertainment. This type of performance offers therapy.Selected Bibliography

Melvin L. Butler, Island Gospel: Pentecostal Music and Identity in Jamaica and the United States (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2019).

Andrew Legg, “A Taxonomy of Musical Gesture in African American Gospel Music,” Popular Music 29, no. 1 (2010).

Braxton D. Shelley, “Analyzing Gospel,” Journal of American Musicological Society 72, no. 1 (2019).

Queer Fado and Nationalism: Going Beyond the Gendered Genre with a Queer Perspective

Excerpts provided below. Please write for permission to use.“The true fado is always sad. Usually in the minor, it retains even in the major the melancholy character associated with the minor. It may be wild, finely exultant in its sadness, seeming to revel in tragedy; or, more striking a note of pathetic and almost languid resignation. Its sophisticated cadences breathe a spirit of theatrical self-pity combined with genuine sincerity. It is emotional, passionate, erotic, sensuous, one might day meretricious, and yet, like some rustic courtesan, fundamentally simple and unpretentious. Perhaps this is because these qualities, however irreconcilable to the Anglo-Saxon way of thinking, are nevertheless reconciled in the Portuguese temperament, or at least in one aspect of it.”Rodney Gallop, “The Fado (The Portuguese Song of Fate),” The Musical Quarterly 19, no. 2 (April 1933): 200.Lyrics of fado songs are reflective of the nation, with Portugal and its politics, fado itself, and love as primary lyrical focuses. Fado music is concerned with the saudade, an emotion that captures the longing, nostalgia, and melancholic sentiments felt in life. It reflects those feelings, but amplified, and more constant and concerned with human existence. You can connect the idea of saudade with missing a person or thing that is gone and may never return, like a family member or place. It is often connected to the Portugal of the past, reminiscing on an earlier or easier time. The solemn nature of the music is transmitted lyrically, but to a greater extent, through the instrumental ensemble and performance. Fado calls to the saudade in listeners using its glacial to walking pace. Listeners could tap their foot, slow dance, or just unwind to. The chorus section of many fado songs is in major while the verses switch to minor (or sometimes Dorian mode). Vocals are melismatic, with sustained notes and pauses at the end of lyrical phases. Rubato is heavily used for dramatic and emotive effect.Fado is reflective of the common Portuguese resident, of the working man. It has been referred to as music of the urban poor, and although listeners may be elite or wealthy, the spirit of the music has not deviated from its target audience. The pain of the struggles of life, of the saudade, remains central to fado’s sound and transmittable message. Fado’s lyrical content reflects a balance of the implicit and explicit. The vocal delivery is often harsh, direct in nature, and unambiguous. A song may describe feeling pain explicitly but capture the nature of saudade by implicitly describing the longing, something the singer also captures. The instrumental ensemble has remained consistent, allowing for accessibility and affordability.The future of Fado is reflective, considering the importance of the genre in past decades and how it can evolve to adapt to the needs of Portuguese people now. It is a national music, acknowledging the diversity of its patrons. Considering the recent work of instrumental duo Dead Combo, who use the mournful sound of fado along with music from spaghetti westerns, and fadistas of younger generations, fado’s longevity is evident. YouTube is also a viable vehicle for younger listeners and performers unconsciously navigating “bilingualism, technological expertise, upward socio-economic mobility, and greater degree of exposure to diverse musical genres” as part of their performance and identity formation. The strongest defector of the genre’s limitations is Fado Bicha, a singer/guitarist duo carving out a musical space to elevate queer Portuguese culture and limit homophobia in their seemingly liberal nation.Fado Bicha formed in fall 2017 and have been pushing the boundaries of fado ever since. The duo consists of Tiago Lila, a vocalist who performs (sometimes in drag) as Lila Fadista, and guitarist João Caçador, who played guitar in fado ensembles prior to playing exclusively with Lila. Fado Bicha, which translates to Queer Fado, started with performances in small LGBTQ positive spaces, like nightclubs and venues hosting drag shows. Lila was struck by the act of singing his nation’s genre: “the experience of singing with the Portuguese guitar was very strong. I was shaking all over, I felt goose bumps all over my head."Lila aimed to take the negative associations with the slur/term ‘bicha’ and transform it into a liberal statement of self-expression since coming into ownership of his sexuality and coming out of the closet. Navigating his childhood and adolescence as a closeted homosexual boy caused him to live with anxiety and depression. As a young adult, he sought to study politics and traditional fado performance. Disliking both of those experiences, Lila ended his training and continued writing songs to perform. Initially Fado Bicha performed solely in drag at small bars and progressed to larger stages, with Lila still donning his trademark glittered beard and dramatically designed eyeshadow.Fado Bicha has amassed a large online following since their formation and have performed at national events like the Lisbon Pride Parade. When they began performing. The duo was initially seen as a joke or parody of fado. Many listeners took to their Facebook page and YouTube video links to mock them or post aggressive rhetoric with homophobic slurs. Some of the negative reception came from homosexual and transsexual men, a surprising development for the group. As time progressed, the unrest subsided and Fado Bicha kept creating and performing throughout: they wanted people to know they were not going anywhere. Fado Bicha represent what fado could encompass, remaking traditional fado songs with new lyrics and creating their own fado songs with the sounds of electric guitar and digital instruments. Fado Bicha is queer fado, but they are also, just fado.Lila grew up listening to fado and found solace in singing along with Amália Rodrigues and other famous fado artists:

I identify with the way (which may be a little romanticized) how [Rodrigues] lived her life, how she lived her despair, her desperation, all the intensity. Artistically, I’m like her son, like so many others. She is a fadista I always listened to and that is my great reference.

It is apropos then, that Lila uses the bones of Rodrigues’ “Lisboa Não Sejas Francesa” to express his distaste with his nation’s racist ways in “Lisboa Não Sejas Racista.” Rodrigues’ song asks Portuguese people not to take the ways of the French and to remain loyal to their own traditions. Her song calls for listeners to remember their identity as Portuguese people, and Fado Bicha’s rendition maintains the same aim. Both songs present a message relevant to the issues of their release and describe ideas that affect the majority, if not all, of Portuguese residents. Fado Bicha’s ode to end racism calls out Portuguese’s past, saying racism is “so 1500s,” and asking people to remember how “you swept to the corner the ones who were children of the Empire,” in reference to African ancestors. The song then names two favela or slum-like areas where darker residents who immigrated from other nations were forced to reside in the 1970s. Its current status as a tourist magnet is also troubling to the band, who recognizes the nature of people to forget their past when it paints the nation in an unfavorable light. The area still possesses a negative stigma as a place taxi driver will not drive through at night, inhabited predominantly by African immigrants who struggle to find work and turn to dealing drugs.Both Rodrigues and Lila present a politicized fado. Potentially Rodrigues’ reputation as a performer and public figure, and adherence to other cultural norms made her message more palatable for listeners than Fado Bicha’s. Lila’s mode of performance, often in drag with a full face of colorful makeup, stands in rebellion of these norms, challenging idealized Portuguese masculinity, reflective of his once closeted sexuality, and flagrantly displayed in an almost playful manner to demonstrate his ownership of the genre that molded him throughout his childhood – fado is queer too, and fado belongs to him as much as it belongs to the women and dark skinned people he advocates for in his music. Lila serves Rodrigues’ legacy by challenging acceptable standards of expression, allowing fado to function as it should, as a mode of communication and representation of the people who make and listen to it.Dr. Lila Ellen Gray recognizes fado as Portugal’s national music, a folk music first attributed to the urban poor that grew to cover the qualms of every man. But a national music should change as its people do, as the times do – adapting to the needs of the nation presently while still reflecting the identity of the people’s journey. Technology (including digital communities) and gender need to be further studied in relation to fado and its changing sound. Fado is malleable, as all musical genres are. Artists like Fado Bicha push the boundaries of their nation’s folk music to demonstrate that dated music can evolve along with its nation and its people. Fado belongs to the common man who is gay, straight, and trans. The common man dresses with a multiplicity of wardrobe options. Lila’s lyrical focuses go beyond his queer identity, calling out the oppression of women and racism, which showcases his ownership of Portuguese identity and desire for all to receive equality. The common man is an advocate for his fellow citizen. There is no one way to be Portuguese, and there is no one way to make Portuguese music.BibliographyKimberly DaCosta Holton, “Fado in Diaspora: Online Internships and Self Display Among YouTube Generation Performers in the U.S.,” Luso-Brazilian Review 53, no. 1 (2016): 213.

John Hutchinson, “Inside Lisbon’s Drug Traffickers’ Slum…,” Dailymail.co.uk, November 12, 2014.

André Soares, “Fado Bicha: How to Get Fado Out of the Convention Closet,” Vice.com, March 2, 2018.

Ana Santillana, “The Queer Fado of Portugal is Called Fado Bicha,” EFE.com, October 31, 2019.

Jamaican Dancehall Masculinity

Coming Soon

Debussy and Parisian Musical Consumption at the Fin De Sicle

Coming Soon

The Soft Battle Cry of an independent Christian tour

Coming Soon

Trying to Tremor: Alternative Identity and Alternative Music in São Miguel

I was invited to give a talk on my first visit to Sao Miguel, which I chose to focus on the music festival I attended and the embodied separation from the familiarity (and safety) of home during my time in the field. While only excerpts are provided, I delved deeper into ideas of being an ethnographer, confronting and challenging notions of privilege, and producing beneficial resources despite the culture shock that is typically accompanied with an initial visit to a field site.

The Black Atlantic Traversing African American Popular Music

This work was recently presented at the 2022 Columbia Graduate Music Scholarship Conference. It is an ongoing work but I was honored to have the opportunity to present. Thank you for watching.

This video features excerpts of my presentation on Verzuz from 2021. Please write for permission to use any contents in the video.